Winter Homes for Beneficial Insects

When the weather cools down and the flowers fade, you might wonder: what happens to all the insects buzzing around your yard all summer? Just like birds and mammals, pollinators and beneficial insects have their own strategies for surviving winter. Knowing where they go, and how to help them, can make a big difference in how many show up next spring to keep your garden thriving. At the same time, not every insect is welcome, so it is important to encourage the helpers while managing the pests.

How Pollinators and Beneficial Insects Overwinter

Different insects use different strategies to survive the winter. Some migrate, some tuck themselves away, and others rely on the next generation to carry on. Understanding these strategies can help you support them in your garden. Here are a few common examples:

Bees

Honey bees often steal the spotlight, but Idaho hosts around 700 native bee species. Unlike social honey bees and bumblebees, most native bees live solitary lives, with nearly 70% nesting underground.

Many overwinter as larvae or pupae inside hollow stems, soil burrows, or leaf litter. Bumblebee queens hibernate underground, while honey bees stay in their hives, clustering and vibrating their wings to generate warmth.

Butterflies and Moths

Monarchs famously migrate south, but many other species survive winter as eggs, caterpillars, pupae, or adults tucked into bark crevices, leaf piles, or other protected spots. These hidden stages allow them to emerge in spring, continuing the vital work of pollination.

Ladybugs and Lacewings

These garden heroes hibernate as adults under bark, in rock crevices, or inside leaf litter. Come spring, they emerge ready to feast on aphids and other pests, keeping your plants healthy without chemical intervention.

Ground Beetles and Spiders

While spiders might make some gardeners nervous, they are essential predators, controlling pests like aphids and flies. Many spiders and ground beetles overwinter in soil, mulch, or tucked under plant debris, quietly maintaining a balanced ecosystem in your garden.

How You Can Help Provide Habitat

A few simple adjustments to fall cleanup can make your landscape much more insect-friendly:

Leave the Leaves: A light layer of fallen leaves insulates overwintering insects and provides food for next spring’s caterpillars.

Create “Soft Landings”: The space beneath trees is valuable habitat for many beneficial insects. Planting a bed under your trees helps support them. Learn more about it here.

Save the Stems: Hollow stems are prime nesting and overwintering sites for native bees. Wait until late spring to cut back perennials, as most bees won’t emerge until night temperatures consistently reach at least 50°F.

Offer Natural Shelter: Brush piles, rock piles, and ornamental grasses provide safe nooks for insects to hide through winter.

Add Nesting Sites: Bee hotels, logs with drilled holes, or patches of bare soil give solitary bees places to nest.

Think Layers: A mix of trees, shrubs, flowers, mulch, and groundcover creates year-round shelter and food sources.

Leaves, brush piles, dead stems, and patches of bare ground aren’t just “messy corners.” They are critical winter housing for pollinators and beneficial insects, helping ensure a thriving, resilient garden come spring.

But What About the Pests?

Not every insect is a friend. Aphids, squash bugs, and Japanese beetles also overwinter in soil, debris, or plant matter. So how do you encourage pollinators without giving pests a free pass?

Be Selective with Cleanup: Focus your tidy-up efforts where pests like to gather, such as near vegetable beds or around heavily infested plants. Compost or remove that debris.

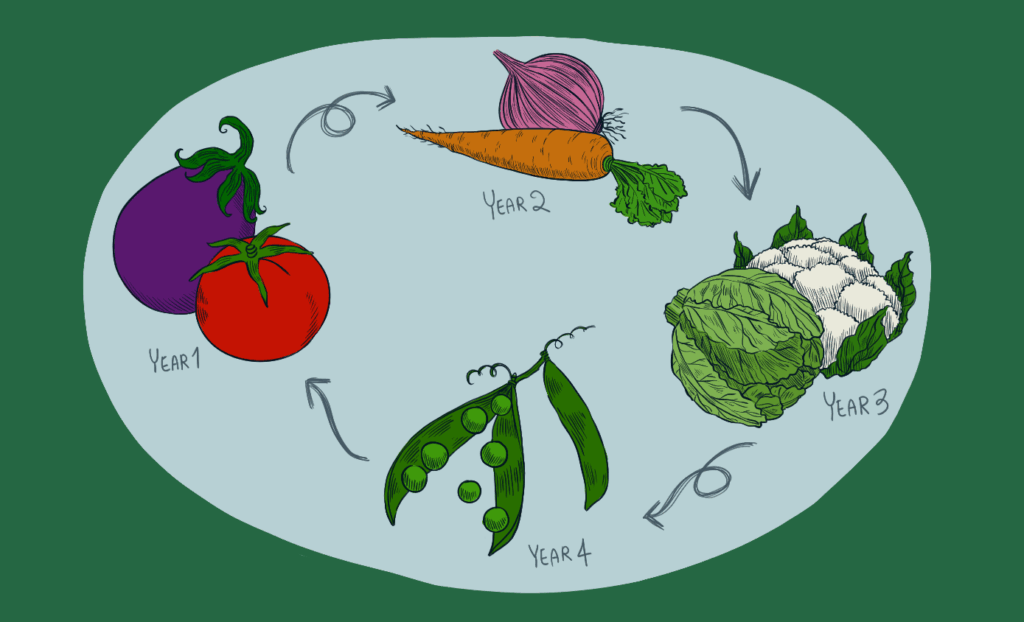

Inspect and Rotate Crops: If you had pest outbreaks in your veggie garden, remove crop residue and rotate next year’s plantings. Many pests are host-specific, so rotation breaks their cycle.

Encourage Predators: Ladybugs, lacewings, and birds will help keep pests in check. Leaving some habitat for them ensures natural balance.

Use Mulch Wisely: Rock or bark mulch can deter certain soil-dwelling pests but may reduce nesting space for ground-nesting bees. Mix and match based on where you need protection versus pollinator habitat.

Plan a “Pest Patrol”: Early spring is a good time to check stems and soil for signs of pest eggs or larvae before they hatch.

Not Sure if It’s a Friend or Foe?

Some insects are tricky to identify at a glance, and it gets even harder because their forms can change so much between life cycles. For example, the larvae of many beneficial insects look nothing like their adult forms. Ladybug larvae, with their long, spiky bodies, are often mistaken for pests even though they eat aphids by the dozens.

If you are not sure whether you are looking at a helpful pollinator or a potential pest, do not guess. Snap a photo or collect a sample and send it to the University of Idaho Extension office. Their experts can help with identification and give advice on whether to encourage, relocate, or manage that insect.

Keep Fire Safety in Mind

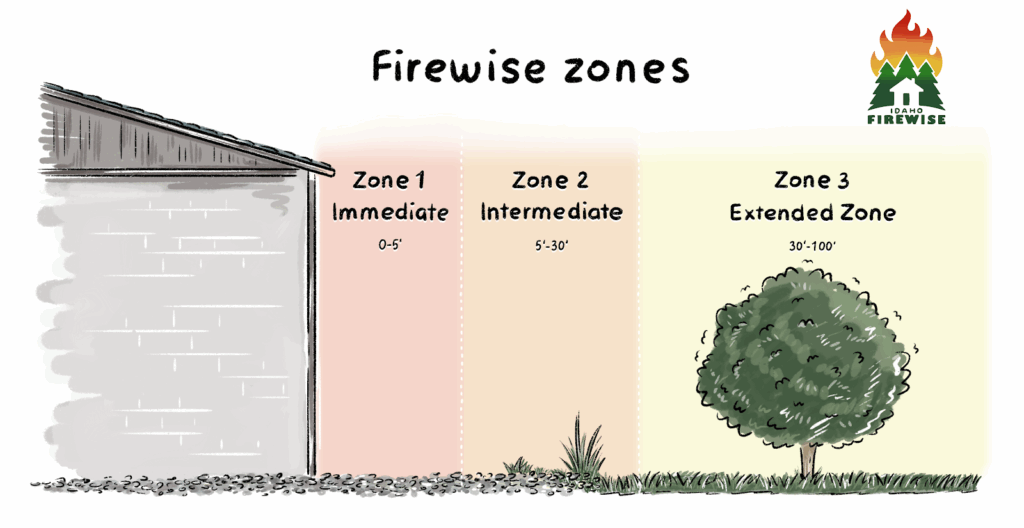

If you live in a fire-prone area, it is important to balance habitat with safety. A firewise landscape means thinking carefully about where you leave stems, brush, and leaves. Follow these tips to protect both your pollinators and your property.

- Near Structures (first 30 feet): Keep this zone tidy, clear away flammable debris, prune shrubs and trees, and avoid brush piles close to your home.

- Farther Out in the Yard: Dedicate areas to pollinator and wildlife habitat, leaving stems, logs, and leaf litter where they can safely provide shelter.

- Create Transitions: Use green, well-watered plants or less flammable materials like rock mulch or walkways as buffers between habitat areas and structures.

A Balanced Approach

The goal is not a perfectly pest-free yard, because that is neither realistic nor healthy for the ecosystem. Instead, aim for balance: provide winter shelter for pollinators and beneficial insects, while managing pest-prone areas with strategic cleanup and crop rotation. And if you are in a fire-prone region, use a firewise approach to place habitat where it is safest. By learning where your insects go in winter, you can set the stage for a healthier, more vibrant garden come spring.

CATEGORY

10/03/2025

a word from our viewers